How Sears Lost Competitive Advantage – Beware of This Fallacy

In a time when the competition has become increasingly difficult, it's more important than ever to develop a competitive edge. This is something Sears, the former retail giant, has struggled to do.

Developing a powerful competitive advantage is great.

But it’s easier said than done you’d probably say.

As an ecommerce manager you know it’s a constant battle to keep ahead of your competition.

It’s a struggle for resources, expertise, and more.

But what if we could show you how to find that advantage—that edge that you need to outperform your competition?

The good news is, we can. And we’ll illustrate it with a story.

How Sears Lost Competitive Advantage

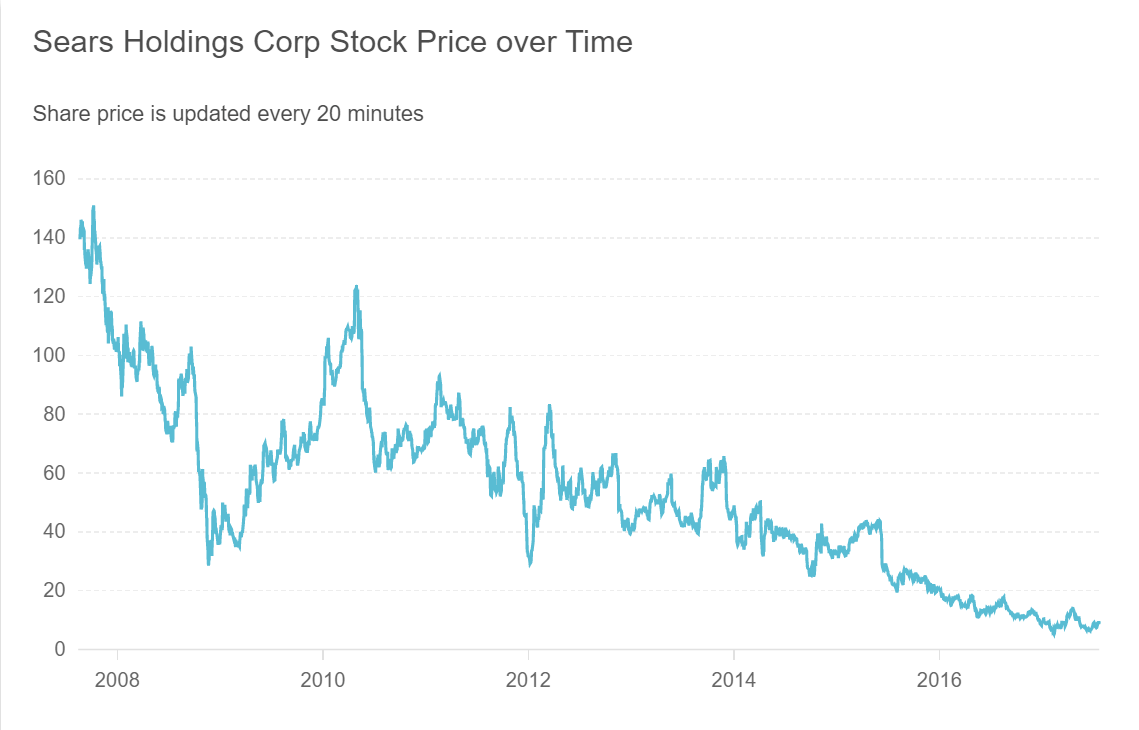

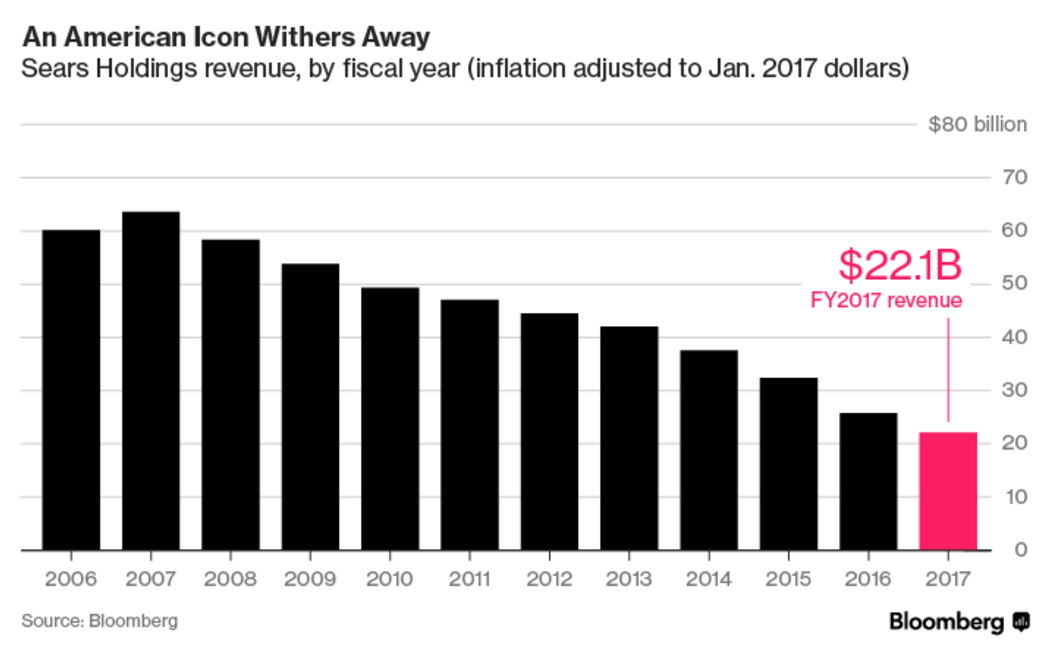

It’s difficult to imagine how a company could fall from such an incredible competitive advantage to near bankruptcy.

Some blame the failure on management, while others say it was Amazon’s fault. We think there’s something else to consider.

In his article, we’ll pull a priceless lesson from the story of Sears, Roebuck & Company. Our purpose isn’t to criticize, point a finger, or declare the giant down for the count.

Rather, our desire is to identify the real culprit and warn today’s ecommerce VP’s and ecommerce managers not to make the same mistake.

You must look closely to see the real culprit. Like so many business failures, the Sears catastrophe began with a logical fallacy.

Did Poor Management Kill Sears?

In 1960, one in every 200 U.S. employees were on the Sears payroll, and one in three Americans enjoyed the benefits of a Sears charge card.

In 1973, the company’s new headquarters building was completed, and the Sears Tower gained the title of tallest building in the world.

Nobody could have imagined then that the giant would soon be toppled.

Most modern analysts blamed CEO Eddie Lampert and his apparent raiding of the combined Sears/Kmart dynasty. A Bloomberg article says “Sears and Kmart have been slowly dismantled by Lampert.”

By 1990, Sears lost its perch completely, when Walmart stripped away the title of “World’s largest retailer.” Of course, another startup company – Amazon – would soon join the race and change the course of retail shopping altogether.

Did Amazon Kill Sears’ Competitive Advantage?

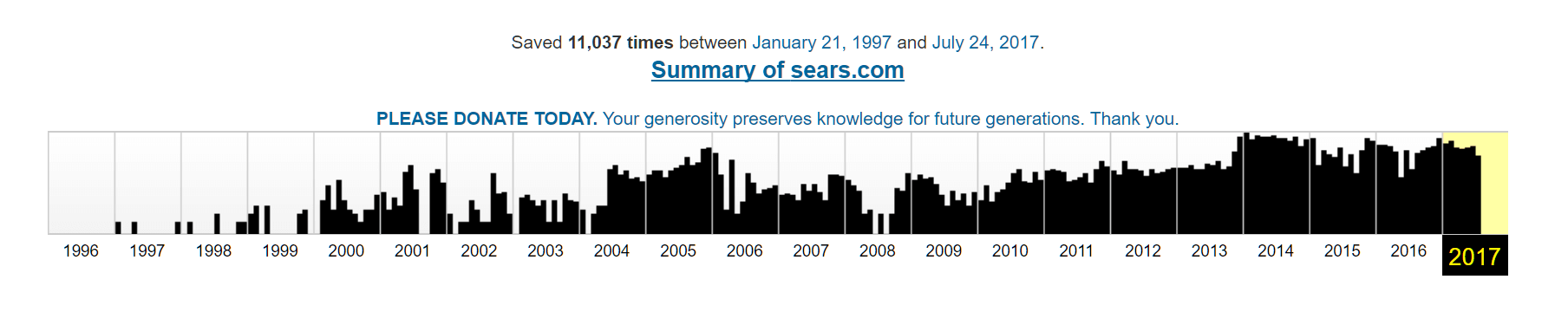

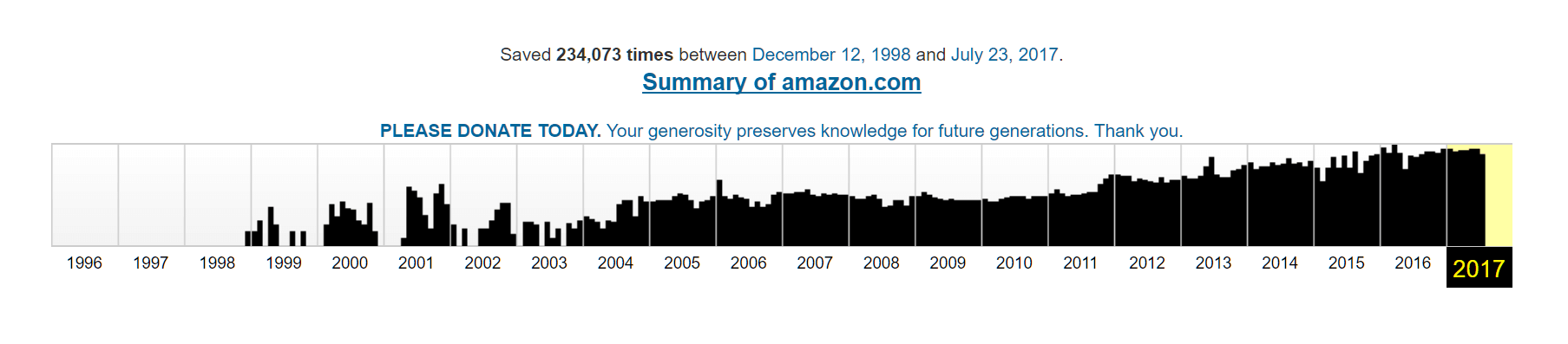

Here’s a bit of internet trivia for you: Sears was online before Amazon was founded.

Sears, CBS, and IBM launched the Prodigy online service in 1988. At 20 seconds into the 30-second Prodigy advertisement (see below) you’ll see an early online link to the Sears site.

Walmart, in comparison, didn’t get serious about the internet until 2000-2001.

This Prodigy commercial (see above) from 1990 shows a link to Sears online.

Jeff Bezos didn’t invent online shopping. What he did do was leverage it successfully. Sears could’ve easily done the same – except for a critical error in thinking.

Jeff Bezos didn’t invent online shopping. What he did do was leverage it successfully. Share on XWe believe that’s the real reason behind the demise of Sears (and many other companies too).

Here’s why.

The Logical Fallacy That Doomed Sears Still Exists Today

Logical fallacies are flaws in reasoning. They sound plausible, but close examination finds a distortion in the premises that lead to an error in the conclusion.

Undoubtedly, there are other thinking errors at play when companies (and individuals) choose badly. Few of us love to make mistakes on purpose. And since we don’t have a logician on staff, we won’t claim to have this nailed… but the error it seems to us to be most in play for ecommerce is termed “Fallacy of Division.”

It goes like this:

- Ecommerce offers excellent potential for revenue growth

- Our company launched an ecommerce website

- Therefore, we can expect a huge growth in revenue

Something critical gets missed in this thought progression: ecommerce does, indeed, offer excellent potential – but it’s only potential.

If one is to reap the benefits from ecommerce, then it’s necessary to pursue a rigorous optimization protocol to seize that opportunity.

Most companies have yet to develop a competent optimization strategy. Therefore, most companies are severely underperforming in their ecommerce efforts.

Sears was one of the first companies to embrace ecommerce. Yet, management allowed the Fallacy of Division to fool them into thinking being online was enough.

It is not.

Enjoying this article?

Subscribe to our newsletter, Good Question, to get insights like this sent straight to your inbox every week.

An online presence can actually hurt a company that isn’t utilizing the principles of user experience (UX) and digital experience optimization (DXO) to adjust the online presence to the chosen audience.

Those in charge of marketing strategy for Sears allowed complacency to lure them into thinking they had covered all the ecommerce bases simply by being online.

And you wouldn’t believe how many VP’s of ecommerce still feel that way today. If you’re not the one in your company stuck in the Fallacy of Division, you probably know exactly who is.

We find few companies not afflicted by the error.

How to Avoid Ending Up Like Sears

We’ve looked at the two most common reasons given by business analysts for the decline of Sears, Roebuck & Company. Sears was the crown jewel of retail selling for decades but has all but self-destructed over the last 20 years.

Competition – even competition as formidable as Amazon – doesn’t destroy a company. Walmart has survived, even thrived, in the face of the same competitive threats faced by Sears, and Sears had the ultimate competitive advantage over both Walmart and Amazon. The brand was firmly embedded in the hearts and minds of its customers. We believe the demise of Sears can be traced back to Prodigy and the first Sears website.

Management was taken in by the Fallacy of Division. They believe that ‘being online’ was enough – that being an early adopter of ecommerce would put and keep them in the lead. There’s a HUGE difference, though, between ‘being online’ and succeeding online.

Without the fundamentals of optimization in place and a deep concern for user experience, being online can hurt you more than help you.

Without a deep concern for user experience, being online can hurt you more than help you. Share on XHere are five checkpoints to get you in touch with your company’s inner Sears. Hopefully, you’ll find it missing entirely.

5 Checkpoints to Evaluate Your Company’s Ecommerce Health And Competitive Advantage

Ask yourself these questions. If you don’t know the answer, ask someone who does. If nobody knows, that’s a really bad sign. Find out and schedule this check up weekly.

1. What is the load time for your home page?

The longer your web pages require to load, the less chance you’ll have of gaining visitors. Today’s prospects won’t wait around for a slow-loading site. They’ll move on. You can check your load time here: Pingdom Website Speed Test. Test your most popular entry pages. All should load within a few seconds.

2. What is the load time for your primary competitors?

Since speed is a primary factor in user experience, knowing how well your competitors are doing gives you a first indicator of how embedded they are in the Fallacy of Division. Take it further by benchmarking for competitive analysis.

3. What are your key performance indicators (KPIs) for the success of your website?

Many companies track site visits and not much else. They assume that getting plenty of traffic means success. That is the Fallacy of Division in action. Put up some content about women in Yoga pants, and you’ll get plenty of visits – but will those visitors become customers? There should be a handful of KPIs you’re tracking rigorously. What are they? Read this: Top Five Analytics Reports for Ecommerce.

4. How and how often are you conducting A/B tests?

You want to beat the competition, but can you beat yourself? We’ve seen companies operate on nothing more than gut feelings. And while going with your gut is sometimes the best way to make a decision, you can be right more often by relying on data-driven information. What you think doesn’t matter nearly as much as what your customers think. Your company should be testing intelligently and often. We urge you to form a culture of experimentation.

5. Do you know the basics of optimization?

Ask your team about optimization essentials. Ask them how important they think optimization is to the bottom line. Going back to the ‘plenty of traffic is all we need’ fallacy, see how many people in your department know the average order value, the average break-even point, and how many customers are required each month to reach it.

Then calculate your current conversion rate and use this tool to have some real fun with numbers. It will show you how bumping up the conversion rate slightly can boost ROI significantly. Use it to get your team pumped about finding ways to get way more out of what you already have. Most companies don’t need a new website. They need a new strategy for optimziation and UX.

Don’t Follow the Sears Example – Fight the Fallacy

Sears eventually came around and began making intelligent, data-driven changes to their site. They woke up to the fact that getting online and succeeding online isn’t the same goal. By then, they’d already lost market share and had begun the slippery slide to defeat. Sears could’ve had it all. Sears could still be on top of the tower. They had a competitive advantage, and they had the first opportunity.

We’re not hammering Sears or the Sears management team. Hindsight is always 20/20. Our aim here is to encourage you to get firmly in the game. Do it now. Do it today. Use the 5-point checklist above to assess your current standing, then do whatever needs to be done to rid your company of fallacy. Share this article with your team and your peers.

Enjoying this article?

Subscribe to our newsletter, Good Question, to get insights like this sent straight to your inbox every week.

About the Author

Jon MacDonald

Jon MacDonald is founder and President of The Good, a digital experience optimization firm that has achieved results for some of the largest companies including Adobe, Nike, Xerox, Verizon, Intel and more. Jon regularly contributes to publications like Entrepreneur and Inc.