How to Test Your Pricing Strategy Without the Ethical Minefield

When clients ask us about price testing, we show them a smarter path: pricing research that protects your brand while delivering the insights you need.

We’ve heard it many times before. “Can we A/B test pricing?”

It’s tempting. The allure of real-time, live data showing exactly which price point converts better feels like the holy grail of product optimization. Fire up your testing platform, split traffic between $29 and $39, and let the numbers tell you what to charge.

But price testing is an ethical and legal minefield that can damage customer trust and put your brand at risk.

After 16 years of optimizing digital experiences, we’ve seen this scenario play out dozens of times. A client comes to us excited about testing prices, we dig into what that actually entails, and we end up recommending something entirely different: pricing research.

The difference matters. A lot.

Why we don’t recommend traditional price testing

While A/B price testing isn’t explicitly illegal in most jurisdictions, it occupies a murky grey area that should make any brand leader pause.

The legal landscape

In the United States, price testing is generally legal. The Robinson-Patman Act prohibits certain forms of price discrimination, but its scope is narrow, primarily applying to business-to-business sales of commodities where different pricing harms competition. For most consumer-facing businesses, the Act rarely applies, and violations are difficult to prove.

In the European Union, however, the situation is different. According to EU law, charging customers differently based solely on their nationality is illegal. Even in random A/B tests where nationality isn’t the determining factor, if a French customer pays more than a Belgian customer for the same product, you could face fines if complaints are filed with the European Consumer Centre.

Recent research published in the Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management highlights how pricing executives must now navigate the triangulation of legal constraints, ethical considerations, and algorithmic decision-making when setting prices.

The consumer perception problem

Beyond legality, there’s the court of public opinion.

A 2022 study from Phiture found that different generational groups react very differently to personalized pricing. While Gen X consumers sometimes try to “game the system” (clearing cookies or using incognito mode to search for better deals), many Millennials and most Boomers react negatively when they discover they’re being charged different prices than other customers.

The Instacart case proves this isn’t theoretical. A Consumer Reports survey conducted in September 2025 found that 72% of Instacart users did not want the company to charge different prices to different users for any reason.

When the investigation revealed the extent of the price testing, customers described feeling “manipulated,” “deceived,” and said they were “not as trusting of a company that practices that.” One volunteer specifically said: “All prices should be the same for everybody, whether you’re rich or poor… some people are going to have to fight back against that system.”

Within weeks of the investigation’s publication, Instacart discontinued the practice entirely, a clear signal that the reputational risk outweighed any revenue optimization gains.

Most consumers view price discrimination as fundamentally unfair, even when it’s legal. When customers discover they paid more than someone else for the exact same product at the exact same time, trust erodes quickly. And once lost, that trust is expensive to rebuild.

The technical limitations

While platforms like Shopify support native price testing functionality, testing tools typically don’t have the infrastructure to modify your actual pricing across different customer segments reliably. Even if you’re comfortable with the ethical considerations, there are practical barriers.

The margin problem

As expert pricing research from Paddle notes, even legal pricing strategies become unethical when they ignore fundamental business health. Simply optimizing for conversion without understanding contribution margin can lead you to “win” tests that actually hurt your bottom line.

Sure, we might see that Product A sold more units than Product B at a given price point, but which product has better margins? That difference fundamentally impacts whether a price change is actually driving profitability or just revenue.

The smarter alternative: pricing research

After explaining these challenges, clients often ask: “So what should we do instead?”

Structured pricing research. Rather than testing prices live on your site where you’re charging real customers different amounts, conduct research that reveals willingness to pay, price sensitivity, and optimal price points before you go to market.

Pricing research gives you the insights of price testing without the ethical baggage, legal risk, or customer trust issues. Here are the primary methodologies we recommend:

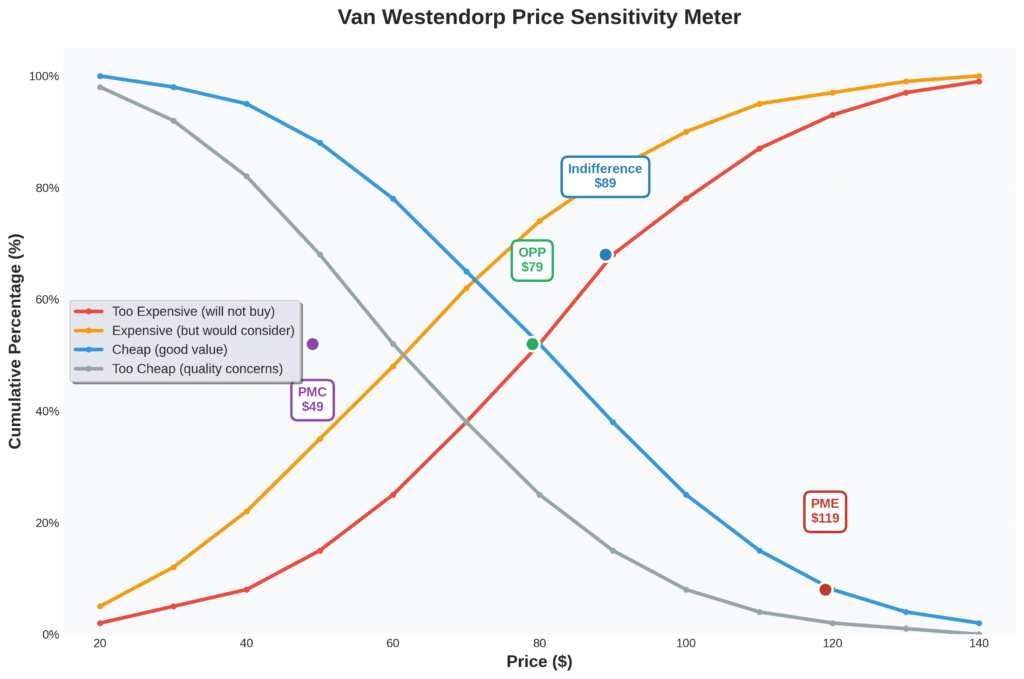

Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter

Developed by Dutch economist Peter Van Westendorp in 1976, the Price Sensitivity Meter (PSM) remains one of the most effective ways to identify acceptable price ranges for products.

The methodology is elegant in its simplicity. You survey your target customers with four key questions:

- At what price would you consider this product too expensive to purchase?

- At what price would you consider this product expensive, but still worth considering?

- At what price would you consider this product a bargain?

- At what price would you consider this product so inexpensive that you’d question its quality?

By plotting cumulative responses to these questions, you can identify several critical price points:

- Point of Marginal Cheapness (PMC): The intersection of “too cheap” and “expensive” lines, which indicates your lower bound

- Point of Marginal Expensiveness (PME): The intersection of “too expensive” and “cheap” lines which indicates your upper bound

- Optimal Price Point (OPP): Where an equal number of respondents describe the price as exceeding either their upper or lower limits

- Indifference Price Point: Where the same number of people think the price is “too expensive” as those who think it’s a “bargain”

According to research from SurveyKing, Van Westendorp is particularly valuable for identifying pricing thresholds and overall market perceptions without putting actual customers in a position where they’re being charged inconsistently.

When to use it: Van Westendorp excels for new-to-world products where you’re establishing an initial price point, or when repositioning an established product in a new market segment. It’s also fast to implement because you can run a Van Westendorp study in days, not weeks.

Limitations to know: The method focuses solely on price perception without considering product features or competitive context. It also can’t predict actual purchase behavior, only price expectations. As noted in research from Conjointly, if your product has multiple configurations or you need to understand feature-specific value, other methods may be more appropriate.

Conjoint analysis

If Van Westendorp is the quick mission, conjoint analysis is the full strategic assessment.

Conjoint analysis reveals how customers value different product attributes, including price, by forcing them to make trade-offs between product profiles. Rather than asking “What would you pay for this?”, conjoint presents respondents with complete product profiles that vary across multiple dimensions (features, brand, price, etc.) and asks them to choose which they’d buy.

For example, a project management software might test profiles varying:

- Number of team members included (5, 15, or 50)

- Storage capacity (10GB, 50GB, or 250GB)

- Integration options (3, 10, or unlimited)

- Price ($19/month, $49/month, or $99/month)

Respondents see sets of 3-4 profiles at a time and select their preference. The pattern of choices reveals the relative value of each attribute, including price sensitivity.

Choice-based conjoint (CBC) is particularly powerful for pricing research because it simulates realistic purchase scenarios. Respondents don’t know you’re primarily interested in pricing; they’re just choosing products they’d actually buy. This approach delivers more honest insights than directly asking about willingness to pay.

Why it works: Conjoint lets you measure price elasticity by brand, understand optimal feature-price combinations, and run market simulations to predict revenue and share. Research from GLG shows that with conjoint data, you can model hypothetical scenarios: “If we add this feature and increase the price by $10, how many customers will we gain or lose?”

When to use it: Conjoint shines when you need to understand how price interacts with product features, or when you’re pricing complex offerings with multiple tiers or bundles. It’s the gold standard for SaaS pricing strategy because it captures the reality that customers evaluate price in context, not isolation.

What to expect: Conjoint requires more upfront investment than Van Westendorp, both in study design and sample size. You’ll need larger respondent pools (typically 300+ for reliable results), and the analysis is more sophisticated. But the insights are proportionally richer.

Segmentation and historical data analysis

Sometimes the best pricing insights are hiding in your own data.

Before running any new research, we always recommend examining your existing customer base through a segmentation lens. Different customer segments often have dramatically different price sensitivity.

Research from TRC Insights shows that price elasticity, the measure of how demand changes with price, varies significantly across customer segments. Enterprise buyers might be relatively price-insensitive (inelastic demand) for mission-critical tools, while small businesses might be highly price-sensitive (elastic demand) for the same product.

By analyzing your historical data, you can identify:

- Which segments have the highest lifetime value at different price points

- How acquisition cost varies by price tier across segments

- Retention patterns that indicate whether pricing is aligned with value delivery

- Upgrade and downgrade patterns that reveal price ceiling and floor effects

One telecommunications company we know of analyzed years of customer data to understand price elasticity by segment. They discovered that their “small business” segment was actually three distinct sub-segments with wildly different price sensitivities:

- one that behaved like enterprise (low elasticity)

- one that behaved like consumers (high elasticity)

- and one in between

This insight led them to redesign their entire pricing strategy with separate offers for each sub-segment, ultimately increasing revenue by 10%+.

When to use it: Always. Historical data analysis should be your starting point for any pricing decision. It’s low-cost (you already have the data), fast, and often reveals surprising patterns.

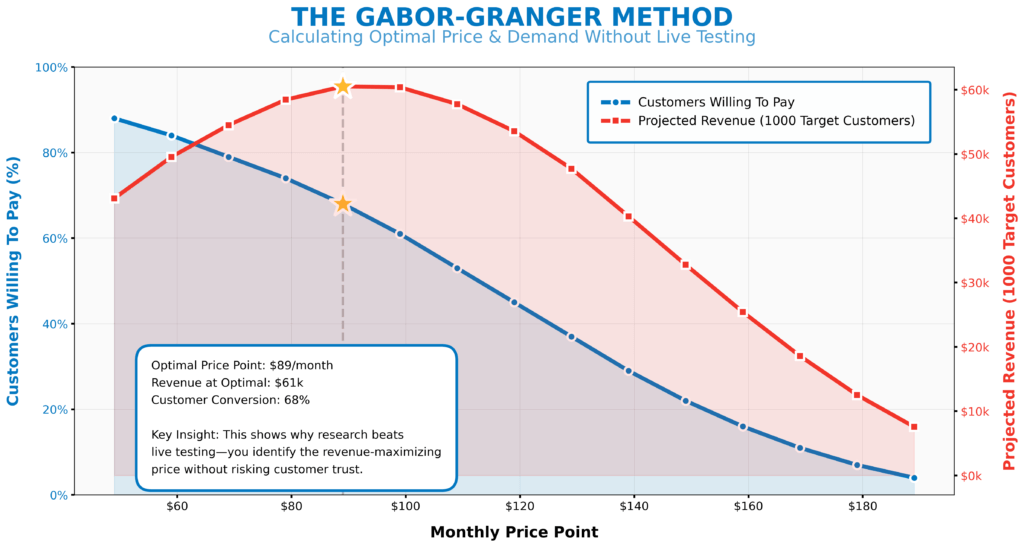

Gabor-Granger method

For a more direct approach to estimating demand curves, the Gabor-Granger method offers a middle ground between Van Westendorp and conjoint analysis.

The process is straightforward: show respondents a product at a specific price and ask if they’d buy it. If yes, show a higher price. If no, show a lower price. Continue until you map out their individual purchase threshold.

Aggregate these responses across your sample, and you can build demand curves that predict:

- The percentage of your market that will buy at each price point

- The revenue-maximizing price

- The volume-maximizing price

- Price elasticity at different levels

This can be particularly useful when you need quick market assessments and want to focus specifically on price sensitivity without evaluating multiple product attributes simultaneously.

When to use it: Gabor-Granger works well for single products or when product attributes are already determined, and you need to optimize pricing specifically. It’s faster than full conjoint but more direct about pricing than Van Westendorp.

Understanding price elasticity for better decisions

All of these methodologies ultimately help you understand price elasticity, how changes in price affect demand for your product.

Price elasticity is typically expressed as: % change in quantity demanded ÷ % change in price

Products with elastic demand (elasticity > 1) see large changes in demand with small price changes. Think luxury goods, or products with many substitutes. Products with inelastic demand (elasticity < 1) see relatively stable demand despite price changes. Think of necessities or products without good alternatives.

Understanding your product’s elasticity is crucial because it determines your pricing strategy’s impact. For elastic products, lowering prices can increase total revenue. For inelastic products, you might be leaving money on the table by not charging more.

Here’s what makes elasticity even more interesting: it’s not fixed. The same product can exhibit different elasticity depending on:

- Customer segment: Enterprise buyers vs. SMBs vs. individual consumers

- Time period: Demand becomes more elastic over time as customers adjust their behavior

- Market conditions: Economic downturns increase price sensitivity even for traditionally inelastic goods

- Price range: Products can be inelastic at low prices but highly elastic at high prices

Understanding these nuances helps you make smarter pricing decisions across your entire customer base, not just at a single price point.

A real example: how we approach pricing strategy

Here’s how these methodologies come together in practice.

A B2B SaaS company approached us, concerned that their pricing wasn’t optimized. They had three tiers ($49/month, $149/month, and $499/month) that had been set somewhat arbitrarily three years ago based on “what felt right” and competitive benchmarking.

Rather than jumping into A/B testing prices, here’s the path we recommended:

Phase 1: Data analysis

We started by analyzing their existing customer data:

- Segmented customers by industry, company size, and usage patterns

- Calculated lifetime value and retention by segment and tier

- Mapped upgrade/downgrade patterns to understand price ceiling effects

- Identified which features correlated with willingness to pay premium prices

This revealed that their “mid-market” segment was actually two distinct groups with different needs and willingness to pay.

Phase 2: Van Westendorp study

We ran a Van Westendorp survey with 400 prospects and recent customers across identified segments. This quickly established:

- Their $49 tier was perceived as “too cheap” by 30% of respondents, potentially signaling quality concerns

- There was an acceptable price range between $79-199 for their middle tier

- Their top tier had room to increase to $599-699 based on value perception

Phase 3: Conjoint analysis

With price ranges identified, we ran a choice-based conjoint to understand:

- Which features justified premium pricing

- How different customer segments valued different feature bundles

- Optimal price points for proposed new tiers

The conjoint revealed that their original three-tier structure was actually constraining revenue. There was demand for a fourth tier at $799/month for enterprise features, and their middle tier could be split into two offerings at $99 and $199.

Results

The company implements a new four-tier pricing structure ($69, $119, $239, $799) based on the research. Average revenue per customer would increase 23%. Customer acquisition would actually improve (lower entry price brings in more customers who later upgrade). Retention holds steady despite price increases because the value alignment was better

This approach would take 8 weeks, and the cost would be well worth it compared to the potential brand damage of customers discovering they’d been charged different prices in an A/B test, or the opportunity cost of not optimizing pricing at all.

Making the case for pricing research internally

If you’re reading this thinking, “this makes sense, but my team really wants to just A/B test prices,” here’s how to make the case:

Frame it as risk management

Price testing puts your brand reputation at risk. Pricing research gives you comparable insights without exposing you to customer backlash, legal concerns, or PR problems. Maintaining customer trust through transparent, ethical pricing practices is crucial for long-term profitability.

Emphasize the quality of insights

A/B tests tell you which price performed better in one specific context at one specific time. Pricing research tells you why that price works, how different segments perceive value, and how pricing interacts with features and positioning. Those insights compound over time.

Talk about margin, not just conversion

This one resonates with CFOs. Pure price tests optimize for conversion or revenue, but they don’t account for margin variation across products or customer acquisition costs across segments. Pricing research can be designed to optimize for profit, not just revenue.

Point to the technical limitations.

Most A/B testing platforms can’t reliably execute pure price tests anyway. You’d need to implement complex technical workarounds that introduce their own risks. Pricing research is straightforward to implement with existing survey tools.

Pricing strategy

The urge to price test is understandable. You want data-driven pricing decisions. You want to optimize this critical lever for growth.

But the best data doesn’t come from exposing real customers to different prices in an A/B test. It comes from structured research that reveals customer psychology, value perception, and willingness to pay without the ethical complications.

What you can do is test discount codes or promotional messaging. For example, we ran a test for a client where some visitors saw “$50 free shipping minimum,” while others saw “$75 free shipping minimum” or “$100 free shipping minimum.” In reality, everyone had a $50 minimum on the backend, but the messaging encouraged different customer segments to add more to their carts. This isn’t pure price testing; it’s messaging optimization that influences average order value.

We’ve spent 16 years helping ecommerce and SaaS companies optimize their digital experiences. When it comes to pricing, though, the most successful companies skip the shortcuts and invest in research that protects customer trust while delivering the insights they need.

The next time someone proposes A/B testing prices, ask them if they’ve considered the alternatives. The answer might surprise them and save your brand from an expensive mistake.

Let’s talk about your pricing strategy.

About the Author

Katie Encabo

Katie Encabo is the Customer Success Manager at The Good. She focuses on supporting and improving the experience of top-performing ecommerce and SaaS growth teams as they optimize the digital experience for their users.