Why Industry Benchmarks are Bullshit

Every business is unique. Using competitor data as a benchmark is usually inaccurate. Instead, your focus should be on information you get from customers.

Key Takeaways

By the end of this article, you should have the knowledge and resources to “check the box” in these areas…

- Why competitor data is unreliable and inaccurate

- The value of studying your customers over your competitors

- Goal-setting, testing, and learning are better alternatives to benchmarks

“What is a good conversion rate?” is one of the most common questions we get from clients. In fact, it comes up once in nearly every project, as if there’s a mythical number that can be achieved with the right collection of strategies and techniques.

You’ve probably Googled something like, “What is a good conversion rate for auto parts ecommerce?” or similar. You want to know how to measure the success or failure of your optimization efforts. You’re looking for a growth ceiling, hoping to identify the version of your website that performs the best.

We don’t blame you for this line of thinking. Industry benchmarks are an obvious starting point for anyone looking to set goals. Unfortunately, comparing your conversion rate to the rates of other companies (or the industry as a whole) is meaningless.

We know you want to be data-driven, but simply having data and a goal isn’t enough. How you use that data is what separates a typical company from an exceptional one. And while we love a good goal, craving a singular, decontextualized benchmark is the opposite of organizational maturity.

In this article, we explain why comparing your conversion rate with industry averages and competitor data is impossible and unwise. Then we give you some super smart alternatives to a typical conversion rate benchmark.

Understanding the Dynamic Nature of Conversion Rate

Most ecommerce store owners and managers ascribe to a particularly reductive view of conversion rate. They assume up is good and down is bad; up means more revenue and down means less revenue. They toil to boost their conversion rate and fret when it falls. But this kind of thinking ignores the dynamic nature of a conversion rate.

Like many marketing metrics, the number on its own isn’t helpful. The number requires context. Any discussion of conversion rate should focus on the question, “Why?” Why did it change? Why is it good or bad for you? There are plenty of cases where a falling conversion rate could be the expected outcome of building your brand ecosystem.

For instance, suppose your brand sells through multiple sales channels, including your own website, Amazon, big box stores, and other brick-and-mortar retailers. You sell through those channels because the increased exposure creates higher revenue.

If you were to remove all of your products from those additional channels and only sell through your website, some customers would seek out your online store directly, but many wouldn’t. They would find a similar product that meets their needs wherever they prefer to shop. In this case, your site’s conversion rate would increase, but your overall revenue would fall.

Similarly, we can imagine a situation where a low conversion rate could help you meet your organization’s goals. A new brand, for instance, may not care about their conversion rate as they focus on building awareness. They might purchase billboards, acquire social visits, and invest in other far-reaching but hard-to-track marketing endeavors. Countless ecommerce organizations care more about their share-of-voice than the percentage of users who convert into customers (at least for a while). They want an audience today that they will monetize tomorrow.

This makes conversion rate benchmarking particularly problematic. When you compare your conversion rate to your competitors, there’s no opportunity to explore the “Why?” There’s no way to pinpoint the causes of change. Your competitors operate in a completely different ecosystem with maturity and marketplace dynamics that make comparison meaningless.

Furthermore, conversion rate benchmarking implies that there’s a ceiling to be reached, a maximum point where your ecommerce site operates at peak performance. But who’s to say that any of your competitors have identified the peak? How can you be sure there isn’t room to grow beyond what anyone has achieved?

Imagine, for a moment, that you know – without a shadow of a doubt – the conversion rate average of your industry. You also know that your own conversion rate is higher. You win! No need for optimization, right? Of course not. Even if your conversion rate is higher than everyone else’s, you still want to push it higher. This means everyone else’s conversion rate is irrelevant for your purposes because you’ll strive to beat yourself anyway.

All in all, focusing on your competitor’s conversion rate (whether you’re looking at a single competitor or the aggregate of an industry or sector) isn’t helpful. In many cases, it’s actually a distraction. Yes, some competitive research is helpful, but it shouldn’t dictate your strategy.

In the next two sections, we’ll talk specifically about the limitations of benchmarking yourself against your competitors and your industry: lack of context and questionable accuracy.

Lack of Context: Contributing & Limiting Factors of Comparing Conversions Rates

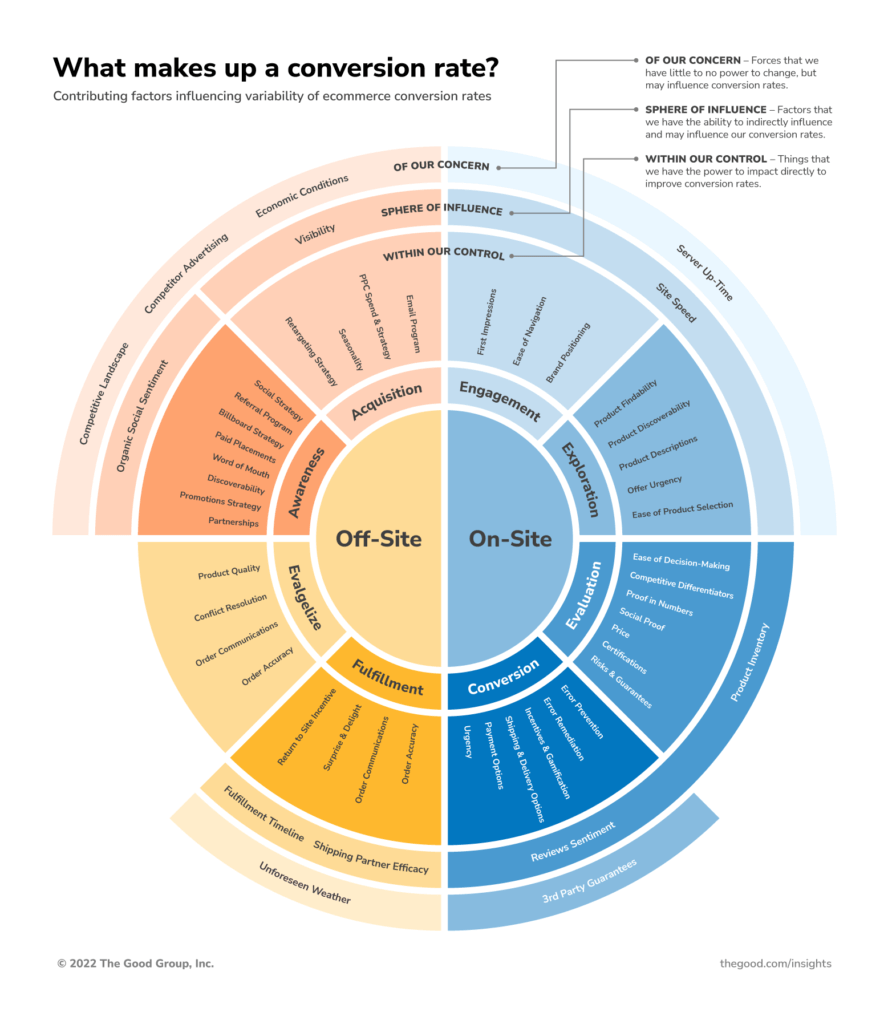

One reason your competitors’ conversion rate metrics aren’t comparable is that they lack context. That context is affected by dozens of contributing and limiting variables, such as the differences between brands, their organizational maturity, acquisition strategy, product mix, and dozens of other factors. In fact, it only takes one difference to make comparison impossible.

Suppose your organization sells eyeglasses for smart professionals and high-income earners. Another eyeglass vendor offers affordable options, targeted at young people and families. In this scenario, the different products, price points, and target audiences create such a difference between the two organizations that comparing conversion rates (or any metric, for that matter) is unhelpful. It’s like comparing apples to snow shoes. There are just too many uncontrolled variables.

The following is a list of many limiting and contributing factors that affect how your site converts. This might seem like an exhaustive list, but there’s even more to be considered (if you can believe it). You may identify factors that relate specifically to your products, audience, and business model. As you read each item, consider how your brand differs from your competitors.

Product

- Product features

- Price (including fees, shipping, etc.)

- Variations and options

- Expanding/shrinking product lines

- Audience target

Market conditions

- Appetite for the product / need variability

- Retail partnerships (partnerships, distribution deals, etc.)

- Competitors (number and type)

- Education around the need

- Brick and mortar availability

- Economic conditions

Acquisition strategy

- Referral program

- PPC spend and strategy

- Third party endorsements

- Unbranded keyword strategy

- Billboard strategy

- Social media presence

- Retargeting strategy

- Paid placements

- Partnerships

Traffic Quality

- Promotions (time and strategy)

- Email program (timing, list size, send frequency, etc.)

- Search engine discoverability (blog, SEO strategy, etc.)

- Brand awareness

- Word of mouth

- In-person (physical) visibility

Site content and efficiency

- Ease of decision-making (bundling, cost, etc.)

- Brand values alignment

- Product descriptions

- Popups and overlays

- Load time

- Ease of navigation

- Competitive differentiators

- Product discovery

- Proof in numbers

- Price to value

- In/out of stock products

- Site bugs, errors, and disruptors

- Social proof

- Shipping (speed of fulfillment, options, etc.)

- Confidence (guarantees, certifications, etc.)

- Ease of product selection

- Price point (in general and vs. competitors)

- Payment options

- Incentives

- Competitor advertising

- Third-party guarantees

Fulfillment

- Fulfillment timeline

- Order communications (post-purchase emails/texts, etc.)

- Unboxing experience

- Shipping partner execution

- Unforeseen weather

- Product quality and functionality

- Expectation-setting during pre-purchase

- Order accuracy

- Conflict resolution

- Surprise and delight

- Incentive to return to site

As you can imagine, those variables create distinct differences between you and your competitors, making comparison pointless. It’s best, therefore, to plan and execute a strategy without trying to imitate your competitors because you are different.

Questionable Accuracy: The Flaw of Self-Reporting Among Competitors

In order to compare your organization’s conversion rate to the conversion rate of another brand, you would first have to convince the other brand to release that data, either to you or some publication that combines it together as an industry average. This kind of self-reporting is rife with incorrect data.

First, your competitors have no incentive to offer accurate information. What’s to gain by releasing honest numbers? If their conversion rate appears high, it may convince the market that the ceiling is higher than expected, causing other brands to invest deeper into conversion rate optimization. Ultimately, the reporting brand could lose sales.

Nor do brands want to report a conversion rate that’s too low, lest their stakeholders, investors, and even their employees lose faith in the organization. They don’t want people banging on their door, demanding to know why the company performs so poorly.

Besides, true conversion rates aren’t impressive numbers by any means. They are usually just a low, single digit. Without understanding what that really means in terms of revenue and in regards to site traffic, it’s easy for the uninformed to misidentify a good conversion rate as low performance.

Therefore, the true conversion rates of your competitors are usually kept hidden. Whatever they publicize is often a sanitized, public-friendly version that avoids causing any problems. In most cases, however, your competitors don’t publicize anything at all. When a publication surveys them for their performance metrics, brands typically refuse to answer.

What’s worse is that when some publications can’t obtain conversion data for the companies they want to report on, they resort to some obscure, ad hoc calculation to work it out for themselves. They’ll grab whatever data they can (such as revenue and site traffic volume), make some assumptions, and then publish their best guess. As you can imagine, these estimates are woefully inaccurate.

Furthermore, even if a competitor offers their true conversion rate, you have to wonder if they calculated it properly in the first place. Do they make incorrect assumptions about what should or shouldn’t be included in their conversion rate? Would it be higher or lower if they used different criteria? Most importantly: Do they calculate their conversion rate the same way you calculate yours?

For instance, suppose Acme Soap (a fictional company) offers a special user account for wholesale partners to place wholesale orders directly through their ecommerce platform. These kinds of sales aren’t usually calculated with the conversion rate because those buyers aren’t the same as traditional shoppers. You might wonder how Acme Soap converts so high, when in truth, they’re just using bad math–including wholesale purchase with their direct-to-consumer ecommerce conversion rate.

This means that any conversion rate offered by another organization is, at best, inaccurate, and at worst, deliberately dishonest. Short of getting yourself hired by one of your competitors and making friends with whomever guards the marketing data, there’s no way to obtain a volume of reliable conversion rate numbers on similar organizations.

Enjoying this article?

Subscribe to our newsletter, Good Question, to get insights like this sent straight to your inbox every week.

Beyond Comparisons: Focusing on Your Customers and Your Own Growth

As the owner or manager of an ecommerce store, we recommend looking beyond conversion rates, never comparing yours to your competitors’ data, and focusing on your own customers. Conversion rate optimization isn’t football. You aren’t trying to win the game by scoring more points than your opponent. In fact, your opponents’ scores don’t matter at all.

Instead, we suggest thinking like a runner. Your goal is to beat the clock, build your own muscles and take every advantage available to beat your best time. When you manage to improve, simply set a new goal, and begin work anew. If you’re focusing on every opportunity to improve like an Olympic athlete would, someday when you are forced to look at competitors, they’ll be left in the dust!

What kinds of advantages and opportunities can you collect? Knowledge from your customers. Unlike studying your competitors, studying your customers is directly applicable. The better you can serve their needs and create better shopping experiences, the higher your conversion rate will climb.

To that end, there are some better questions you can ask that will give you a deeper understanding of your organization’s performance, help you learn more from your customers, and shed some light on what to do to move forward.

Does this mean all benchmarks are pointless?

Not all benchmarks are bad. Competitor and industry benchmarks are pointless for the reasons we explained above, but your own benchmarks are highly valuable. After all, you have to know where you’re starting in order to gauge the effectiveness of your optimization strategy.

Furthermore, drilling down two individual metrics is a better method of benchmarking then looking at your overall conversion rate. For instance, consider the conversion rate of your product details pages or the conversion rates of individual acquisition channels. Studying these metrics is far more actionable because you can quickly generate experiments to improve them.

Is competitive analysis useful at all?

Yes, absolutely. Understanding your competitor’s behavior is useful, but there are healthy and unhealthy ways of looking at your competition.

A healthy way of competitor analysis, for example, would be social listening, where you investigate comments made online about your competitors, and then use those sentiments and themes to inform your own campaigns and messaging. For instance, if your competitor’s customers complain about a common product defect, you might change your product listings, ads, and offers to emphasize how your products lack that defect.

In a case like this, you would be analyzing your competitors while still focused on yourself . You’re like Kobe Bryant, studying tapes of your basketball heroes, identifying what was effective or ineffective (based on traceable outcomes), and adapting their moves to the unique skills you have as a player.

Unhealthy competitor analysis involves blindly copying your competitor’s messaging, strategy, and tactics. In these cases, you aren’t learning or seeking to answer the “Why?” question. You’re just looking for a shortcut, hoping what works for them will also work for you.

Have we reached the limit of our DTC touchpoint?

The problem with identifying a ceiling is that it’s only a ceiling until you push it higher. Growth of a metric is always possible, but you have to consider the cost. Some optimizations offer diminishing returns. Others cost more than they’re worth.

Besides, customer learning never stops. Ever. It does not matter how clearly you grasp your customers’ wants, needs, desires, and problems. There is always something more to learn, which means there’s always a way to improve their experience.

How do we value success?

Putting a value on optimization efforts is actually simple. Will the revenue generated from the optimization program be greater than its cost? In this case, it’s important to think beyond singular sales. A generic conversion rate calculates the rate that visitors make a purchase, but there are other factors that paint a clearer picture of success, such as lifetime value, basket size, average revenue per user, etc.

What is our goal conversion rate?

Once you know your own conversion rate, and have vowed to ignore the metrics of your competitors or the industry, this is the most obvious concern. It’s a great question, too, because it leads you into actionable strategies that can actually push the needle.

Setting a top-level goal for your conversion rate is problematic because, like we said earlier, you’ll always want it to be higher. Instead, it’s better to set goals for individual experiments. These goals will depend on the nature of the experiment (some optimizations will move that needle more than others), your product, and your audience.

Goal-Setting, Experimentation, and Iterative Learning

Instead of using industry or competitor benchmarks, it’s smarter to focus on yourself. This lets you deal with one ecosystem where the variables are controlled, so you can make changes, measure the results, and then deduce reasonable answers to the question “Why?” Ultimately, this means that conversion rate optimization is an entirely internal process.

First, it’s important to have clarity regarding your bigger business goals. This will help you design specific conversion rate goals that serve your broader purpose. For instance, an organization that’s trying to develop a broad network of retail partnerships may only be willing to Increase its conversion rate if it doesn’t cannibalize sales from other channels.

1. Goal-setting

Generally, we suggest focusing on two kinds of conversion rate goals: 1) Goals that help your visitors research your products or services and 2) Goals that help your visitors purchase those products from you. Everything else is secondary to the desires of the customer. This customer-centric view is key to the success of your organization.

In order to adopt a customer-centered approach, management will need to accept an iterative mindset that recognizes the value of testing and data-based decision making and you’ll likely need to employ the services of a conversion rate optimization specialist.

Identify goals that elevate the quality of your customers’ research and buying activities. Listen (to their words and the data of their session) to what they want and give it to them. Do they search for a particular type of content? Perhaps the right content will help. Do customers drop out of your long checkout workflow? Perhaps streamlining it will keep them engaged.

2. Experimentation

Experimentation is the meat of conversion rate optimization. Many ecommerce store owners and managers dive into this part of the process by emulating what they see their competitors doing, without setting proper goals or even understanding the purpose behind a particular strategy or tactic.

Admittedly, experimentation is a tedious and laborious process without the help of a practiced conversion optimization specialist, especially in the beginning. Changes are often small and seemingly short-sighted, but they can add up to big improvements over time.

3. Iterative learning

This is the part of the process that isn’t available when you simply duplicate the strategies and tactics of your competitors. It’s also arguably the most valuable piece of the process because it provides you with the information you need to set better goals and run better experiments in the future. In the same way that your investment account grows faster due to compound interest, learning also expands exponentially.

Imagine that you learn that some of your customers want a subscription version of one of your products. You experiment with a subscription and find it to be successful. Armed with this knowledge, you might explore subscription options of other products, play around with offering bulk sizes, or create a box-of-the-month offering. In cases like this, learning begets more experimentation, which begets more learning.

This is the genesis of the answer to the “Why?” question that we at The Good believe is so critical to the success of any conversion rate optimization plan.

Getting Started

We recognize that our philosophy of benchmarking represents a shift in thinking. It’s tempting to use your competitors as tools to judge your own success or failure within your industry, but these comparisons are always inapplicable and inaccurate.

In order to achieve true success, it’s best to focus on your own conversion rate, set goals, design experiments to creep it upward, and – most importantly – collect valuable information (that only applies to your business and customer) that can help you keep pushing.

If all of this sounds too difficult to manage, you aren’t alone. Countless ecommerce professionals lack the time and experience to implement a truly effective conversion rate optimization program. You’ll find it cost-effective to outsource this function to a team of specialists. Otherwise you’ll be leaving money on the table.

The Good offers a suite of conversion rate optimization services that help you identify why shoppers aren’t buying and fix it. Find out why your website is not converting and how to improve with our Comprehensive Conversion Audit. Increase conversions with a fully managed monthly optimization solution with our Conversion Growth Program™ (most popular).

Small businesses can discover the top conversion blockers costing you ecommerce sales with our Conversion Growth Assessment™. We can also provide expert advice on your user’s behavior, site experience, and more.

Remember: Your organization is unique. Comparing yourself to your competitors by focusing on their benchmarks is an ineffective distraction. Your customers provide all of the information you need to grow your brand.

Behind The Click

Learn how to use the hidden psychological forces that shape online behavior to craft digital journeys that delight, engage, and convert.

About the Author

Natalie Thomas

Natalie Thomas is the Director of CRO & UX Strategy at The Good. She works alongside ecommerce and lead generation brands every day to produce sustainable, long term growth strategies.